Testimony Regarding the Sun Dance

In Teton Sioux Music, Densmore included the following detailed descriptions and testimony about the Sun Dance:

Išnála Wičhá (Lone Man)

Išnála Wičhá (Lone Man) said to the writer:

“When we heard that you had come for the facts concerning the Sun Dance, we consulted together in our homes. Some hesitated. We have discarded the old ways yet to talk of them is ‘sacred talk’ to us. If we were to talk of the Sun Dance there should be at least 12 persons present, so that no disrespect would be shown, and no young people should be allowed to come from curiosity. When we decided to come to the council, we reviewed all the facts of the Sun Dance and asked Wakan´ tanka that we might give a true account. We prayed that no bad weather would prevent the presence of anyone chosen to attend, and see, during all this week the sound of the thunder has not been heard, the sky has been fair by day and the moon has shone brightly by night, so we know that Wakan´ tanka heard our prayer.”

Seated in a circle, according to the old custom, the Indians listened to the statements concerning the Sun Dance as they had already been given to the writer. According to an agreement, there were no interruptions as the manuscript was translated. The man at the southern end of the row held a pipe, which he occasionally lit and handed to the man at his left. Silently, the pipe was passed from one to another, each man puffing it for a moment. The closest attention was given throughout the reading. A member of the white race can never know what reminiscences it brought to the silent Indians— what scenes of departed glory, what dignity and pride of race. After this, the men conferred together concerning the work.

That night until a late hour, the subject was discussed in the camp of Indians. The next morning, the principal session of the council took place. At this time, the expression of opinion was general and after each discussion a man was designated to state the decision through the interpreter. Sometimes one man and sometimes another made the final statement, but nothing was written down which did not represent a consensus of opinion. Throughout the councils, care was taken that the form of a question did not suggest a possible answer by the Indians.

On the afternoon of that day, the entire party drove across the prairie to the place, about a mile and a half from the Standing Rock Agency, where the last Sun Dance of these bands was held in 1882.

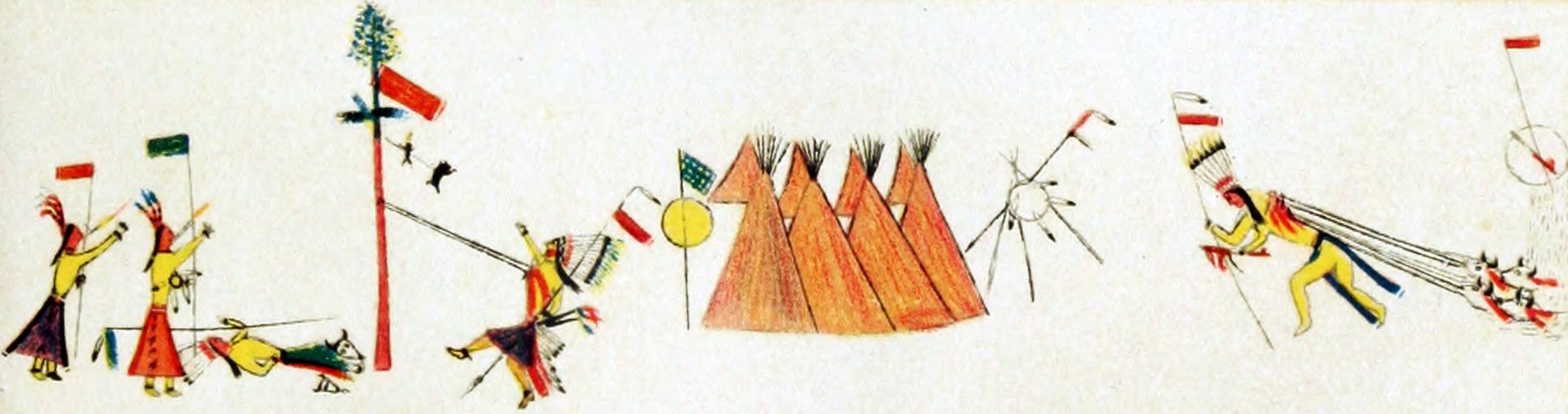

A majority of the Indians who went to the site of the Sun Dance with the writer were men who took part in the Sun Dance of 1882 and had not visited the place since that time. When nearing the place, they scanned the horizon, measuring the distance to the Missouri River and the buttes. At last they gave a signal for the wagons to stop, and, springing to the ground, began to search the prairie. In a short time, they found the exact spot where the ceremony was held. The scars were still on the prairie as they were on their own bodies. A depression about two inches in depth, still square in outline and not fully overgrown with grass, showed where the earth had been exposed for the owáŋka wakȟáŋ (“sacred place”). Only three or four feet away lay a broken buffalo skull. Eagerly, the Indians lifted it and saw traces of red paint upon it—could it be other than the skull used in that ceremony? They looked if perchance they might find a trace of the location of the pole. It should be about 15 feet east of the “sacred place.” There it was—a spot of hard, bare ground 18 inches in diameter.

One said, “Here you can see where the shade-house stood.” This shade-house, or shelter of boughs, was built entirely around the Sun Dance circle except for a wide entrance at the east. It was possible to trace part of it, the outline being particularly clear on the west of the circle; to the east, the position of the posts at the entrance was also recognized. The two sunken places (where the posts had stood) were about 15 feet apart, and the center of the space between them was directly in line with the site of the pole and the center of the “sacred place” at the west of it. More than 29 years had passed since the ceremony. It is strange that the wind had not sown seeds on those spots of earth.

The little party assembled again around the buffalo skull. Mr. Higheagle gathered fresh sage, which he put beside the “sacred place.” He then laid the broken buffalo skull upon it and rested a Sun Dance pipe against the skull, with stem uplifted. He, too, had his memories. As a boy of six years, he was present at that final Sun Dance, wearing the Indian garb and living the tribal life. Between that day and the present lay the years of education in the white man's way. Some of the Indians put on their war bonnets and their jackets of deerskin with the long fringes. How bright were the porcupine quills on the tobacco bags! “Yes, it is good that we came here today.” Pass the pipe from hand to hand in the old way. Jest a little. Yonder man tells too fine a story of his part in the Sun Dance—let him show his scars! Yet the memories, how they return!

One old man said with trembling lips: “I was young then. My wife and my children were with me. They went away many years ago. I wish I could have gone with them.”

A few weeks later, the material was again discussed point-by-point with men who came 40 miles for the purpose. Chief among these was Red Bird, who was under instruction for the office of Intercessor when the Sun Dance was discontinued. He was present at the first council, but some facts had come to his mind in the meantime, and he wished to have them included in the narrative. These men met four times for the discussion of the subject, the phonograph records being played for them and approved, and some ceremonial songs being added to the series. A few days later, a conference was held with five other men, most of whom were present at the council of August 28 and 29. The session lasted an entire day, the narrative which had been prepared being translated into Sioux and the phonograph records played for them, as for the previous group of men. With one exception, all the men present were chiefs.

Throughout this series of conferences the principal points of the account remained unchanged. Each session added information, placed events in the proper order, furnished detail of description, and gave reasons for various ceremonial acts. The councils were not marked by controversy, a spirit of cordiality prevailing, but the open discussion assisted in recalling facts and nothing was recorded which was not pronounced correct by the council as a whole.

A message was then sent to Red Weasel, an aged man who acted as Intercessor at the last Sun Dance, asking him to come and give his opinion on the material. He came and with three others went over the subject in another all-day council. His training and experience enabled him to recall details concerning the special duties of the Intercessor, and he also sang four songs which he received from Wí-iháŋbla (Dreamer-of-the-Sun) together with the instructions concerning the duties of his office. Before singing the first song the aged man bowed his head and made the following prayer which was recorded by the phonograph:

“Wakȟáŋ Tȟáŋka, hear me. This day I am to tell your word. But without sin I shall speak. The tribe shall live. Behold me for I am humble. From above watch me. You are always the truth. Listen to me, my friends and relatives, sitting here, and I shall be at peace. May our voices be heard at the future goal you have prepared for us.”

The foregoing prayer was uttered in so low a voice that the phonogram was read with difficulty. It is uncertain whether the aged man intended that it should be recorded, but as he had seated himself before the phonograph preparatory to singing, it was possible to put the machine in motion without attracting his attention. He began the prayer with head bowed and right hand extended, later raising his face and using the same gestures which he would have used when filling his ceremonial office.

The final work on this material was done with Chased-by-Bears, a man who had twice acted as Leader of the Dancers, had “spoken the Sun Dance vow” of a war party, and had frequently inflicted the tortures at the ceremony. He was a particularly thoughtful man, remaining steadfast in the ancient beliefs of his people. Few details were added to the description of the ceremony at this time, but its teachings received special attention.

Chased-by-Bears’ recital of his understanding of the Sun Dance was not given consecutively, though it is herewith presented in connected form. This material represents several conferences with the writer, and also talks between Mr. Higheagle and Chased-by-Bears which took place during long drives across the prairie. In order to give opportunity for these conversations, the interpreter brought Chased-by-Bears to the agency every day in his own conveyance. Thus the information was gradually secured. When it had been put in its present form, it was translated into Sioux for Chased-by-Bears, who said that it was correct in every particular.

The statement of Chased-by-Bears concerning the Sun Dance was as follows:

“The Sun Dance is so sacred to us that we do not talk of it often. Before talking of holy things, we prepare ourselves by offerings. If only two are to talk together, one will fill his pipe and hand it to the other, who will light it and offer it to the sky and the earth. Then they will smoke together, and after smoking they will be ready to talk of holy things.

“The cutting of the bodies in fulfillment of a Sun Dance vow is different from the cutting of the flesh when people are in sorrow. A man's body is his own, and when he gives his body or his flesh he is giving the only thing which really belongs to him. We know that all the creatures on the earth were placed here by Wakȟáŋ Tȟáŋka. Thus, if a man says he will give a horse to Wakȟáŋ Tȟáŋka, he is only giving to Wakȟáŋ Tȟáŋka that which already belongs to him. I might give tobacco or other articles in the Sun Dance, but if I gave these and kept back the best, no one would believe that I was in earnest. I must give something that I really value to show that my whole being goes with the lesser gifts; therefore I promise to give my body.

“A child believes that only the action of someone who is unfriendly can cause pain, but in the Sun Dance we acknowledge first the goodness of Wakȟáŋ Tȟáŋka, and then we suffer pain because of what he has done for us. To this day, I have never joined a Christian Church. The old belief which I have always held is still with me.

“When a man does a piece of work which is admired by all, we say that it is wonderful; but when we see the changes of day and night, the sun, moon, and stars in the sky, and the changing seasons upon the earth, with their ripening fruits, anyone must realize that it is the work of someone more powerful than man. Greatest of all is the sun, without which we could not live. The birds and the beasts, the trees and the rocks, are the work of some great power. Sometimes men say that they can understand the meaning of the songs of birds. I can believe this is true. They say that they can understand the call and cry of the animals, and I can believe this also is true, for these creatures and man are alike the work of a great power. We often wish for things to come, as the rain or the snow. They do not always come when we wish, but they are sure to come in time, for they are under the control of a power that is greater than man.

“It is right that men should repent when they make or fulfill a vow to Wakȟáŋ Tȟáŋka. No matter how good a man may appear to others, there are always things he has done for which he ought to be sorry, and he will feel better if he repents of them. Men often weep in the Sun Dance and cry aloud. They are asking something of Wakȟáŋ Tȟáŋka, and are like children who wish to show their sorrow, and who also know that a request is more readily granted to a child who cries.

“We talk to Wakȟáŋ Tȟáŋka and are sure that he hears us, and yet it is hard to explain what we believe about this. It is the general belief of the Indians that after a man dies, his spirit is somewhere on the earth or in the sky, we do not know exactly where, but we are sure that his spirit still lives. Sometimes people have agreed together that if it were found possible for spirits to speak to men, they would make themselves known to their friends after they died, but they never came to speak to us again, unless, perhaps, in our sleeping dreams. So it is with Wakȟáŋ Tȟáŋka. We believe that he is everywhere, yet he is to us as the spirits of our friends, whose voices we can not hear.

“My first Sun Dance vow was made when I was 24 years of age. I was alone and far from the camp when I saw an Arikaree approaching on horseback, leading a horse. I knew that my life was in danger, so I said, ‘Wakȟáŋ Tȟáŋka, if you will let me kill this man and capture his horse with this lariat, I will give you my flesh at the next Sun Dance.’

“I was successful, and when I reached home I told my friends that I had conquered by the help of Wakȟáŋ Tȟáŋka and had made a Sun Dance vow. It happened that I was the first who had done this after the Sun Dance of that summer, so my friends said that I should be the Leader of the Dancers at the next ceremony.

“In fulfilling this vow, I carried the lariat I had used in capturing the horse fastened to the flesh of my right shoulder and the figure of a horse cut from rawhide fastened to my left shoulder.

“Later in the same year, I went with a party of about 20 warriors. As we approached the enemy, some of the men came to me saying that they desired to make Sun Dance vows and asking if I would ‘speak the vow’ for the party. Each man came to me alone and made some gift with the request. He also stated what gifts he would make at the Sun Dance, but did not always say what part he intended to take in the dance. One man said, ‘I will give my whole body to Wakȟáŋ Tȟáŋka.’ I did not understand what he meant, nor was it necessary that I should do so, but at the time of the Sun Dance he asked that his body be suspended entirely above the ground.

“Just before sunrise, I told the warriors to stand side by side facing the east. I stood behind them and told them to raise their right hands. I raised my right hand with them and said: ‘Wakȟáŋ Tȟáŋka, these men have requested me to make this vow for them. I pray you take pity on us and on our families at home. We are now between life and death. For the sake of our families and relatives we desire that you will help us conquer the enemy and capture his horses to take home with us. Because they are thankful for your goodness and will be thankful if you grant this request, these men promise that they will take part in the next Sun Dance. Each man has some offering to give at the proper time.’

“We were successful and returned home victorious. Knowing that these men had vowed to take part in the Sun Dance, I saw that their vows were fulfilled at the next ceremony and personally did the cutting of their arms and the suspension of their bodies. I did this in addition to acting as Leader of the Dancers and fulfilling my own vow.

“The second time I fulfilled a Sun Dance vow, I also acted as Leader of the Dancers. At that time I carried four buffalo skulls. They were so heavy that I could not stand erect, but bowed myself upon a stick which I was permitted to use and danced in that position.”

When the work with Chased-by-Bears was finished he went with the writer and the interpreter to the spot where the final Sun Dance was held, a place which had been visited by the council of Indians a few weeks before. The purpose of this visit was that Chased-by-Bears might arrange the ceremonial articles on the sacred place as would be done in a ceremony.

The outline of the sacred place was made clear and intersecting white lines were traced on the exposed earth. A buffalo skull had been secured and brought to the place. Chased-by-Bears spread fresh sage beside the “sacred place” and laid the buffalo skull upon it. He then made a frame to support a pipe and placed in ceremonial position a pipe which had been decorated by the woman who decorated the Sun Dance pipe for the last tribal ceremony. The group of articles was then photographed. Suddenly Chased-by-Bears threw himself, face downward, on the ground, with his head pressed against the top of the buffalo skull. This was the position permitted a Leader of the Dancers when resting during the Sun Dance. After a few silent moments he rose to his feet. The white cross was then obliterated, and fresh sage was carefully strewn over the bare, brown earth, so that no chance passer-by would pause to wonder.

The study of the Sun Dance was finished.